Written by Rodney Likaku

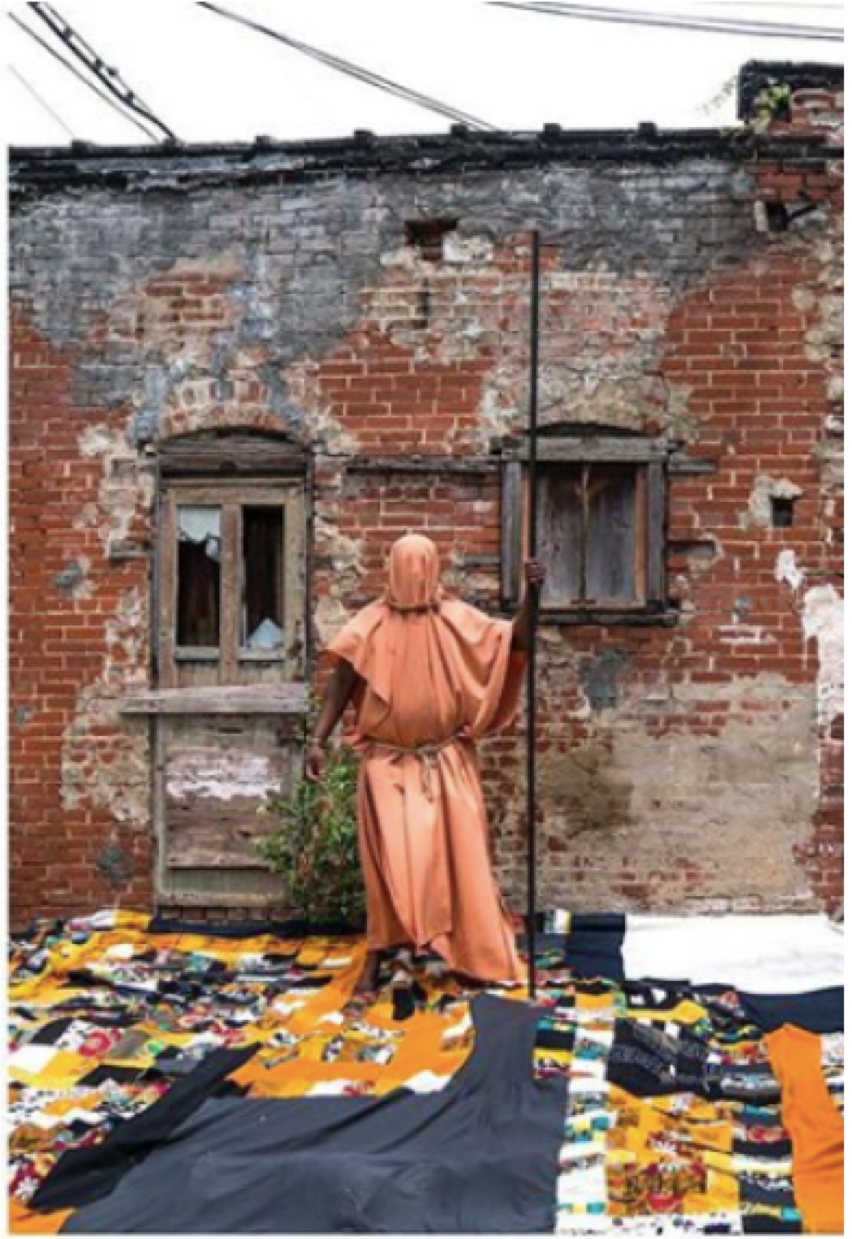

Art by Basil Kincaid

DECOLONISING THE MIND

It is a bit like opening your eyes in in a pool of black oil. Depression. It is almost like catching the flue. You are convinced you are going to die; your friends think you should man-up.

I am going to walk today. Clear my head. I pass through Zomba market and I see boys my age fry thick potato slices in huge pans. They turn the potatoes round-and-around in this liquid purgatory until what was once oil looks like the devil’s urine. Days like today feel like swimming lessons in this liquid art of nothing.

When I get home, I don’t even bother switching on the lights. I fall asleep in the dark.

Outside my window, Satan calls me by name.

It is Tuesday, maybe, my tongue tastes of Monday morning. My mind is dead. It is going to be one of those days when I must paint my own sky blue. Blue like sadness, not like the sky.

I am so far from myself: who am I? Where am I? I have already had a long week.

I have done this dance before, first the sickness from nothing, then it will be the mental paralysis. Soon it will feel like falling through soft clouds; or swimming in baby tears, a masquerade of time past and time present, before the world strangles me, slowly: enough to titillate death, but no too sufficiently to scare off life.

I am black, and I am male. Remember what he said, “it is un-African”—they will tell me to Man-up.

Oh! Man, I know this wolf by name. World meet Depression, my favorite of the pack.

In my head I am trying to be manly, but the brain doesn’t grow muscles to show for its masculinity.

Depression is a skin-deep type of beauty. It is simple to romanticize the experience. This is because it can be poetic, I can imagine likening it to menstruation: saying something like it is sort of bleeding without the commitment to dying. But this a type of poetry without a name. Not lyrical like hamlet, or Prufrock; poetic almost like licking the tip of a razor blade. Isn’t that beautiful?

No.

You see, she, Depression, and I grew up together. The way those kids on TV grow up with their favorite pet. Lately, she seems unwell. It could be my fault, I have been too busy. I hear her howling in the back of my head; soon she will tire of terrorizing me.

***

I shut my eyes tightly. I dream about that day. You boys remember it, right? I am nine, the both of you are seven. Mum is at work, and dad too, I guess. I hold you in your left hand, and I hold you in the right hand. Then I lead us to the small river behind our house, because I promised to teach you how to swim.

You liked that, did you? The maid, Ana-Phiri found us, and later on that evening she tells mom. Mother beats all three of us, especially me. Then she sits and weeps the rest of that night, saying that we are the only thing she has got. She says she is sorry she beat me the hardest, says I am the eldest, and that we could have drowned, and that she could lose us, she could lose me. I sit and comfort her.

Her beating is a bit like depression, a flogging for something that has not happened, from not drowning, a hit for staying alive.

This scene comes in a sequence of variations. In the final version, there is death by water. It is mine.

On land, I wake up. Outside my small house in Ndola, the sun is bright. Inside my brain, the stars shine down. In the heat of summer my mind slowly melts, decaying, and creating cobwebs of memories yet to come.

We sit and cuddle, she and I, Melancholy. I tell her the plan for today: let me go to work, one last time, tonight we die, I promise.

You come into my room after mom manages to fall asleep. You say you are sorry I got hit the hardest, and you tell me that you are thankful I taught you to swim. Me too.

You have a twin so you understand this bond. Depression, too, sometimes comes with its twin. They are fraternal. But they still look alike, Suicide—she started to ask for more attention as I grew older.

Do you remember dad’s friend from up the road? The big man. They found him dangling from a rope.

Father told me, once, that at his funeral they said he died of malaria. You know. Because they did not want to show him as being weak. Whispers around said he was selfish enough to seek freedom, and that it was un-African. We are duty bound to stay alive in a world of pain.

They spoke of dad’s friend’s mental illness as the thing you speak of without a name, a monster. She is ugly, but she is here. Suicide crawls onto my bed too, she wants to play, tonight, I say, promise?

I promise.

She licks my face with her tongue: to feel the warmth of the other world closely, to touch a flame and not feel the burn.

Depression climbs up too. I flip her over, and see why she is having a mood lately—she is pregnant.

We need new names. Let the guessing begin: maybe one will be Hypertension. Maybe the other will be Anxiety. The third will be Over-Sensitive for a boy. The last could be Moody. I fall asleep. This time I drown on land.

The sun keeps its promises, tomorrow arrives, and I have to go teach this class. I work as a lecturer at Chancellor College, “I am sorry I am late, I felt like death this morning”, I let the laughter die down. No, the beautiful ones are not yet born. This is simply an undergraduate African-American literature class.

A hand shoots up, “Sir”

“Don’t call me that, I am not a knight” more laughter. I do not think it was funny, I was serious.

“What is the point of learning slave history—when slavery is over?” Is it? I think.

“Turn to your course outlines “, It is going to be a long year.

***

I want to tell you something, but I forget. Tomorrow, I promise.

“Wakwiya ndi mfiti”, My grandmother says that demons are restless. Master is always restless. Master has a PhD. Welcome to the hell that is Malawian academia.

If you don’t have a doctorate, you are a slave. This is Doctor Jim Crow, came back from Stellenbosch University and now runs this place like a plantation. It is like baby-sitting on steroids. I dare not make a sound.

It is a bit bizarre that those who fight so hard against colonization, no longer need the colonizer to do it to themselves. Modern day Malawi is Victorian Britain. I have class.

Much of Post-colonial theory is built on pointing fingers, but a lot of the enemy is within himself.

Thirty-six pairs of eyes stare at me.

“We will be reading Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man”. We spend some time talking about how the negro was said to be absent. That you could not know what he was thinking. They laugh.

I spend the rest of the day in my study, dreading going home and being alone. Master flings open the door. Master is a newly minted doctor, but master cannot diagnosis his own sickness.

He thinks he is God. I think he is educated. Those two are not synonymous. This is why I get punished.

“You” He says. Never refers to me by name. I should remember to tell this to the class: slave masters always gave their own name to the slave.

“Yes” I look up. He has nothing to say. Just wanted to make sure that I was not causing trouble. I hear him whistle as he walks away. Behind him, a cracking whip of his doctoral title somehow still echoing.

***

“Then there is the idea of social death put forth by Orlando Patterson”

Same hand, “Social death?”

“Yes. Strip the slave of everything, including his name, no title”

“So how would they refer to them?”

“Anything. For a while, maybe even as, “you!” The students think slavery is weird.

I assure them it is in the African past.

***

Where does a country look when it has lost its mind? For while we thought it was in academia. Educated ignorance is the funniest joke to tell. I enjoy master thinking he is intelligent—and that he is—but not enough to know that one can be ultra-smart, and yet still completely clueless.

I have been avoiding work this week. The department is splitting itself in camps. Master refused to sign someone else’s conference paper leave document. He recruited a new slave-breaker without consent from the rest of us. I should remember to tell the class about this,

“When we get to the narrative of Frederick Douglas you will say that the best way to keep slaves was to ensure that they could be turned against each other”. I take no questions, I am tired, I leave straight for home.

In the meeting the next day, I hear Master take credit for an idea we both came up with. In class that afternoon, I tell the undergrads that slaves were made to feel privileged to serve the master. I assign as an assignment, the Aristotelean Hierarchy and how it informs the logic of the oppressor.

The students secretly call me “jailer” for the rest of the semester. The irony makes me smile when I hear this.

Before I leave for work, Master sees me laugh with a British member of staff. There is a part of him that harbors the Desdemona complex. He calls me “black by mistake”. I pretend not to hear him. Master is a postcolonial scholar. In a postcolonial university. In an English Department. But Master is in chains.

I head home, same route, same potatoes are frying, same hell. Upon arrival, I am greeted by a litter of puppies. The twins sit around the newborns, Anxiety looks like her mother; she is troublesome, this one. She wants to walk to the future and so plans too far ahead to be reasonable. Depression holds her down. This only makes Moody confused.

We all sit and cuddle on the bed. Me and my small monsters.

My mind thinks in satanic verses.

Behind me, the steady purr from the hounds inside my head beckons to more tomorrows that feel like death, warmed, up.

Today is tomorrow. Black coffee. My muscles are on fire. The day dreams of nothing, shapes so elaborate. Grasped by you-know-what.

I spread myself on my bed, then the fetal position, I recognize each hound one-by-one, by name.

Underneath is the box of mental crayons. Yellow—to shade in the light, because in this head, here, the sun doesn’t shine. Black—by mistake, for having this disease, he said. Blue—like a septic wound, not like flowers.

***

I remember now. That thing I wanted to tell you.

***

There was a downhill slope outside the gate in our house at Sunnyside. We weren’t allowed to ride our bikes outside, but when we refused to die of water, we would instead try to die on land.

We were racing. I was losing. So, I stood up on my bike and let go of my hands so that it looked, to anyone watching, like was crucified on thin air, on a moving bicycle. I have never felt so free like that.

The dogs chased behind my bike, and when I reached the bottom of the slope, I stopped, and they run towards the next fast, moving thing.

This story was supposed to end on chapter nine. I promised myself to only write the last chapter a few minutes before my 29th Birthday. If there is a chapter ten, then I survived.

All the therapy, meditation, and kindness saved a life. Now I must do the same for someone else.

So when?

Tomorrow, I promise.

The End